The passages are taken from Edward S. Abdy's Journal

of a Residence and Tour in the United States (3 vols, London, 1835)

During the "age of Jackson", dozens of Europeans toured the United States, and went home to publish books about it. As an anthology of such accounts said, "America was the China of the nineteenth century --described, analyzed, promoted, and attacked in virtually every nation struggling to come to terms with new social and political forces." [Abroad in America, xiii]. The works of British travelers in particular, were then pirated, and read by Americans, who then denounced and ridiculed them.Edward Abdy's book would have surpassed all in arousing the ire of the Americans, except it was never printed in America (until 1969, when the Negro Universities Press did an academic reprint). Harper Brothers was, according to Abdy, about to print it, but was scared out of it. Indeed, they would have made themselves a conspicuous target, during the waves of mob violence against African Americans and critics of slavery, that rent the mid 1830s, for half of the book dealt with the United States' mistreatment of Americans of African descent. Cities like New York, Boston, and Philadelphia, erupted in violent sympathy with the south and its "peculiar institution", but Abdy's book dwelt most directly on just such northern parts of the U.S., and their own extreme racism. He considered it an outrage in itself, and a key part of the system that upheld slavery "the negro will always be treated as a brute, till he is acknowledged to be a man." [vol 2, p36].

The critique (or "criminal indictment" as he put it) is the more poignant for coming from a man who did not come with an attitude of superiority "I can say, with the utmost sincerity, that I left England with a wish to do justice to America. I thought her character had been misrepresented, and I was anxious to collect facts that I might adduce in her vindication on my return." [vol 1, p391]. He in fact described Americans as having, in many cases, an instinctive politeness superior to that cultivated by the European.

But ultimately, the portraiture of American crudeness; the incessant spitting, and so forth, came to seem, to Abdy, trivial, and hardly worth discussing.

"To be quizzed and caricatured for vulgarity, is intolerable to the same people, who seem not to know, or not to care that you despise them for their prejudices. Hint to them that they eat pease with a knife, and they are highly enraged: tell them that their conduct to the "niggers" is inhuman and unmanly, and they laugh in your face." [vol 2, p76,77].When Abdy described the interiors of African American homes, he painted a very well-rounded picture of a people with a sense of humor, warm familial relations, and the strength to resist. One man had "A slight touch of the braggart about him was not ill-suited to the wildness of the scenery [... which] might fairly be set down to that giddiness of mind which self-elevation from the most abject state is apt to produce in the strongest heads." They are as far as can be from sentimentalized "victims".Though he had his foibles, Abdy is basically just such a wise guide as one might want, when having to face the horrifying spectacle of American racism in the 1830s. In speaking of American vanity and defensiveness, he wrote:

It is amusing to see how personal vanity assumes the garb of patriotism; and, while it thinks it is merely paying a just tribute to national glory, is seeking its own gratification. Even the smile which this weakness elicits, proceeds from the same feeling. [emphasis added].

Edward Abdy came to America, like Tocqueville, with a group sent to study American prison, but he soon went off on his own investigations. Throughout his travels, he investigated the lives of "Africo-Americans", as he chose to call them, and the attitudes and treatment accorded them by "white" Americans.He pursued this investigation as assiduously as Tocqueville studied the workings of American government. He spoke to barbers, porters, laundresses, and ex-slaves, gathered in little farming communities. He visited Prudence Crandall's school on three separate occasions, from near its inception up to its disbanding under pressure of violence, arson, boycotting, and legal persecution.

He often ate or took tea in the Africo-American homes of Cincinnati, Philadelphia, New York, and elsewhere; often having to persuade his hosts that it was all right to sit down and eat with him, a white man. He also made a thorough study of the Colonization Society, which he came to detest, the Garrisonians, and the Lane seminarians, who were opening schools for blacks in Cincinnati, and sat on the boxes of Stagecoaches, learning the attitudes of the drivers -- some surprisingly sympathetic to blacks, even in the south; others contemptuous or even vicious.

Abdy spent his first few weeks in New York, where he visited various institutions, and spent some time with black Episcopal minister Peter Williams to learn what "Africo-Americans" thought of the African colonization movement. The reports he got, from two of Williams' parishioners, were extremely negative. One had lost his wife and a child to illness, and was in danger of losing another (such stories would accumulate; they were all too typical). He also met with William Lloyd Garrison who was departing for England to raise money.

Next, he traveled to New England, where he had a long visit with David and Lydia Maria Child. He attended a meeting of the Colonization Society, which he didn't like, and a meeting of abolitionists, which he did. He got to know a black minister from Baltimore, there to raise money for his church. He sought out the abolitionist Samuel J. May in Brooklyn, CT, and Prudence Crandall, who was trying to maintain a school for girls of (all or partly) African descent.

He next followed the Erie Canal route, making various stops, and meeting an Africo-American in Utica who professed to have worked a con, whereby a partner "sold" him to a West Indies planter, and they absconded and split the money. He spent a couple of days admiring Niagara Falls, before crossing over to the "free soil" of Canada, where he reported blacks living ordinary lives without harassment.

Back in New York, he attended an 'African' church, and a Colonization meeting, where a black protester was thrown out. He was present at the founding, in October 1833, of the New York Anti-Slavery Society, --nearly broken up by a mob instigated by James Watson Webb's Courier and Enquirer, and Solomon Lange's Gazette (cf. Leonard Richards' Gentlemen...)

He stayed in New York through the winter, talking with some supposed runaway slaves languishing in the jail, and meeting Hester Lane, who had purchased eleven people out of slavery, apparently unrelated to her. She had gotten a steady living out of "discovering a new mode of coloring walls". Before leaving the city, he also got to know Susanna Peterson, whose young son saved two boys from drowning in a skating pond, and drowned himself trying to rescue a third. He was disgusted to learn that "not one of the relatives of either of the boys [rescued] had been near the bereaved mother", though she was accosted by a man two or three times, trying to persuade her to immigrate to "pestilential" Liberia.

In the spring of 1834, Edward Abdy began a long trek through the upper south. In Baltimore, he called on Mr. Levington, the black minister who had been fundraising in Boston, who described the limited success of his mission, and an overture by the Colonization Society, trying to send him to Liberia.

At Gadsby's in Washington, he was "shocked beyond description at the idea of being surrounded by" the slaves who worked there. He listened to the waiter who brought him breakfast, who said "If the owner of my wife, should endorse a bill, and the drawer fail, he would perhaps sell her to obtain money; and we should never see each other again."

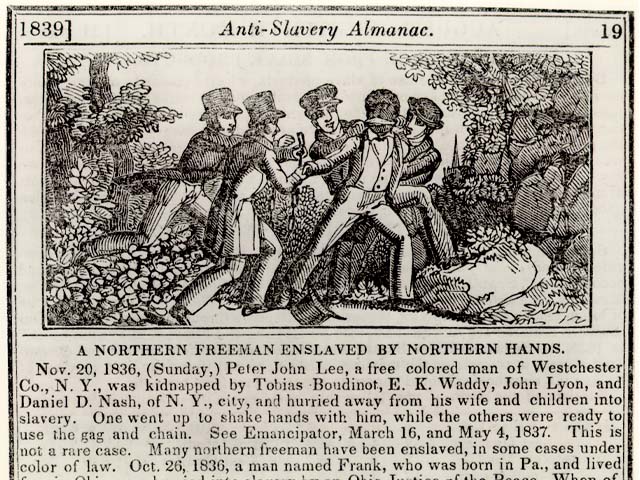

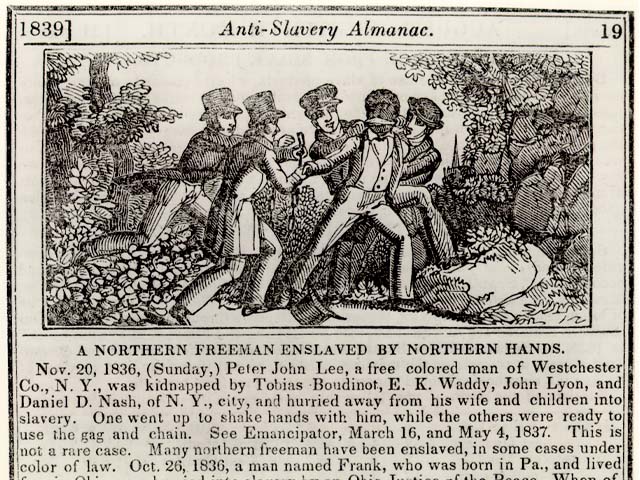

He saw a slave pen, heard much of the activities of kidnappers; of the presumption of being a runaway, should any black person be encountered without papers, and the danger of being "claimed" by any unscrupulous white man; of people being tricked out of their freedom papers; of slave coffles, etc. He visited congress and later, the President, who he found surrounded by flatterers and "toad-eaters".

In Virginia and Kentucky, he observed southern mores, and spoke to inn-keepers, slaves, a few free blacks (generally nervous to appear on friendly terms with a foreign white man). Onboard a steamboat, he observed African Americans actually having conversation and jokes at dinner (white Americans were notorious for silently bolting down meals taken in public places), and he traded theories with them about why their white fellow countrymen behaved so strangely at table.

He finally crossed back into the free states at Madison, Indiana, where an Africo-American barber told him of a small farm community of 129 blacks. While Abdy was with them, someone brought word to the "head of the clan" of an escaped slave hiding out in a cabin nearby. A group, including Abdy, went out to see her, and were told a dreadful story of having been legally free, but kidnapped as a child. This was her second escape, she having nearly frozen during her first try, in the dead of winter. The little group raised money for the woman, and one of them planned to use his deceased wife's free papers to spirit her off to Canada.

From Madison, Edward Abdy took a steam-boat to Cincinnati, where he "looked out, as I invariably did... for one of the despised caste" among a "boisterous" crowd of mostly white porters. There he read advertisements for runaway slaves, and a bit of lewd scurrility, in Judge Hall's Western Monthly Magazine, directed at the Lane seminary students who were going out into the local black community, starting schools, and, in some cases, living among them. The article asked "how far these young theologians intend to carry their tender intercourse with 'Afric's sunbrown'd daughters.' We hope their intentions are honorable, &c."

Again, he observed the Colonization Society, which put his patience "to the most severe test", with lies (if Abdy's first-hand witnesses are to be believed) about the "prosperous and increasing trade", the wonderful effect the colonists were having on the native Africans. The next day he "bent my solitary way towards the enemy's quarters."; i.e. to Lane Seminary, where he met Theodore Weld, and James Bradley, who was taken from Africa as a child, purchased his freedom for $700, and was attending Lane (and later Oberlin). He also met an unnamed southerner who since coming to Lane, had given up his two slaves, and was paying for the education of one of them, and he listened to horror stories of slavery from the several southern students turned abolitionists.

In the Cincinnati black community, he "found their houses furnished in a style of comfort and elegance much superior to what I had seen among whites of the same rank," and must have spent hours with one family, listening to their experiences with slavery. In fact from the various accounts he gave, he must have spent many days visiting these families. He also heard another damning report about Liberia from a black Baptist minister recently returned from there.

After Cincinnati, Abdy started for the east, but heard of another "colony" of blacks from Virginia, part of a group of over 300 who were freed by their owner, an Englishman named Gist. He had to win over their confidence, as they had suffered much persecution from their white neighbors, but he spent a couple of days there interviewing them. He then backtracked to Cincinnati, to try to give some unspecified help to the Gist colony; also, hearing that that a fragment of the same group had settled near Hillsborough, he went there.

On his way east, he saw and described the black communities of Chillicothe, Zanesville, and Pittsburgh, and the promising development of antislavery in Zanesville and Pittsburgh.

Back, at last, in the Northeast, he stayed in Philadelphia, getting to know the wealthy and respected James Forten, as well as other more humble members of the African American community there. At one point he "went in search of" his boardinghouse waiter, who was missing and feared to have been kidnapped. He spoke to another African American, just returned from Liberia, who described a country where "most" died of fever, and many of the survivors mistreated the natives, rather than "elevating" them as they were supposed to.

It was during this summer that two of the worst anti-black riots of the 1830s took place, in Philadelphia and New York. Abdy was apparently not in the middle of them, but he provides many vignettes from the mouths of those who were, as well as some less direct testimony.

He spoke to black coachmen about why they kept the 'best and neatest' vehicles, and got to know barbers who 'in handling a colonizationist, are as ready with their logic as with their razors.' He was appalled to observe that Quakers, other than Hicksites, possibly, practiced the same sort of segregation in their services as the other denominations (I suspect his acquaintance with reformers in England led him to expect better of them). He collected many stories of slaves ransoming themselves, or outwitting their masters, and sadder stories of kidnappings and slaves who went 'back to their chains' rather than violate a promise.

Returning to New England, Edward Abdy revisited Prudence Crandall's school, whose numbers had been cut by a third, as their neighbors perpetrated ever more frightening acts of harassment.

In Providence, Rhode Island, Abdy paid a visit to William Ellery Channing, a Boston Unitarian minister (the chief influence on Unitarianism in his time), whose essays were widely read. Abdy wanted to know why this great moral leader had so little to say about the appalling treatment of African Americans in his own back yard. The resulting conversation is reported in great detail. Abdy found him woefully ignorant of how blacks were treated in this country, and what they were like. He kept exposing the flaws and apparent hypocrisy in Channings ideas, and bolstered the printed transcript with quotations from Channings' writing, that seemed to imply a nobler mind than the one before him. Shortly afterwards, Channing delivered a sermon against slavery, that grew into a famous printed essay. Harriet Martineau credits Abdy for this (Retrospective of Western Travel)

Abdy followed some abolitionists, including William J. May, to the new Noyes Seminary, in Canaan, NH, intended from the beginning to serve black as well as white students. While there, he heard of the suppression of the Lane Seminarians by the school's executive committee -- and the mass exodus from Cincinnati to Oberlin.

After this, he passed through Canterbury, CT one last time, to find the school finally broken up, and the students being sent home. In New York and Philadelphia, he found black communities ravaged by white riots against them; churches burned; homes wrecked, and some dead and more fled. Apart from extensive words on the riots, he tells of meeting Christiana Gibbons, a "Philadelphia woman of 'pure African blood and royal descent'"; and her dignity and "willingness to engage in any work that did not carry moral degradation."

"It seemed as if the demon of cruelty was to accompany me back even to England", he writes in the final pages. In Portsmouth, England, where they landed, the ship's black waiter "waited upon me during three or four days that I was detained by illness", and it was only then he learned that the man was secretly married to a "fair, young Englishwoman" who had been onboard the ship, and that in New York, he had had to visit her secretly in her brother's house; otherwise, "perhaps both husband and wife would have fallen victims to popular fury".